The housing struggle then and now

Housing struggles by African Americans some 40 years ago hold lessons for those fighting for justice amid today's foreclosure crisis.

THE GROWING number of mortgage foreclosures in African American communities has not only created a housing crisis among Black homeowners, but one for Black renters in properties where the owner has defaulted as well.

According to several recent news reports, the number of foreclosures on multifamily rental dwellings across the country is growing. The Washington Post noted that in Washington, D.C., some 475 foreclosure proceedings were initiated against owners of multifamily rental properties during the first three quarters of 2009, versus 458 for all of 2008.

In Los Angeles, 78 buildings with five or more units--a total of 1,344 units--were in foreclosure in the first three quarters of 2009, versus 49 buildings with 432 units in all of 2008 and 13 buildings in 2007.

In New York City, housing experts predict that between 50,000 and 100,000 units of housing are at risk because of "upside down loans"--that is, when owners owe more on their mortgages than the value of the property.

The Post also noted that across the country, between 65 and 75 percent of multifamily buildings could "face problems refinancing at their current rates," raising the specter of a wave of foreclosures directly affecting the rental market. In Chicago, the Chicago Reporter found that two of every three small apartment buildings foreclosed upon are in African American neighborhoods.

Of course, the wave of foreclosures has already had a particularly harsh impact on African American renters. Blacks, especially women, are especially vulnerable to the perils of evictions, and the foreclosure crisis has made that danger even more acute.

For example, the research of sociologist Mathew Desmond on evictions in Milwaukee has shown that while Black women make up 13 percent of the population in the city, they account for more than 40 percent of those who are evicted from rental residences. The New York Times noted similar numbers in other cities.

Many of these evictions of renters are the result of unemployment and other problems created by the recession. But the foreclosure crisis has affected renters who are able to pay their rent.

First, when landlords find that they're losing money on their investment in rental property, they begin cutting back on maintenance, allowing the building to sink into disrepair. And with the rising cost of utilities also cutting into the profitability of rental property, landlords are willing to turn off heat, water and even electricity to save money.

Second, when landlords lose their building, the bank--or whatever entity becomes the new owner--is quick to evict the former tenants. They do so either to raise rents or rehabilitate and sell the building for a profit.

A number of cities have laws protecting tenants from immediate eviction upon the sale of their rental unit to another owner. Even so, new owners are often unscrupulous in their attempts to remove tenants.

For example, in Chicago, which has some of the most liberal tenant laws in the U.S., new owners are supposed to give tenants 30 days notice to move. If the tenant refuses to go, the landlords are required to go through legal eviction proceedings. Despite these legal protections, there have been several documented cases of new owners illegally evicting tenants in Chicago. Owners know that the vast majority of tenants have no idea of their rights and legal protections.

Because of this naked assault on the rights of tenants--and the general crisis in the availability of affordable housing--housing right activists in different cities are beginning to challenge both legal and illegal evictions with protests, moving tenants back into their rental units or housing homeless people in vacant properties.

THE FIGHT over access to affordable and decent housing began in the 20th century, when American cities became the destination for most of the country's population. Indeed, collective and militant struggle against illegal or immoral evictions have coincided with upsurges in political activism and radicalism in the U.S.

Historians have written about the dramatic confrontations in the 1930s between Communist Party activists and members of the community on one side, and landlords and police on the other. The Great Depression left millions unable to pay their rent, but activists showed up at evictions, and moved the furniture and belongings of tenants back into their apartments as quickly as the cops had taken it out.

Much less is known about the dynamic tenants rights movement of the 1960s, which found expression in many cities across the U.S.

The movement focused on reforming tenancy laws that, until the late 1960s and 1970s, completely favored the rights of landlords. But the struggle, an outgrowth of the civil rights and Black Power movements empowered tenants to challenge slum conditions in much of the country's urban housing. They formed tenant unions and physically challenged court-ordered evictions.

Chicago's tenant rights movement became one of the most visible in the country when Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. made Chicago the site of his Northern campaign to highlight racism and discrimination outside the South.

King worked with activists in the Chicago Freedom Movement (CFM), who debated whether to focus on job discrimination or racism and public schools. Eventually, organizers from King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), King himself, and local activists agreed on a target: slum conditions in housing on the West Side of Chicago. They concluded that the problems in housing were closely tied to problems of access to jobs and good schools.

Thus, in the summer of 1966, King addressed more than 50,000 people--mostly African Americans--in Chicago's Soldier Field to outline what the CFM would look like. In his speech, King said:

This day, we must declare our own emancipation proclamation. This day, we must commit ourselves to make any sacrifice necessary to change Chicago. This day, we must decide to fill up the jails of Chicago, if necessary, in order to end slums. This day, we must decide to register every Negro in Chicago of voting age before the municipal election. This day, we must decide that our votes will determine who will be the mayor of Chicago next year...

This day, we must continue our already successful efforts to organize, in every area of Chicago, unions to end slums. Together, we must withhold rent from landlords that force us to live in subhuman conditions.

And let me say, here and now, that we are not going to tolerate moves that are now being made in subtle manners to intimidate, harass and penalize Negro landlords who may own one or two buildings, while ignoring the fact that slums are really perpetuated by the huge real estate agencies, mortgage and banking institutions, and city, state and federal governments.

After the speech, more than 35,000 Chicagoans, most of then Black, marched to City Hall, where King nailed a list of demands related to housing, education and jobs. Part of the CFM's goal was to highlight the unequal living conditions in African American communities created by the existence of slum conditions. To dramatize the point, King moved into a slum apartment on the city's segregated West Side.

The other element of the plan was to organize Unions to End Slums across the city. This was part of a collaborative effort between the AFL-CIO and SCLC to use the "union model" to organize tenants and expose conditions of poverty in cities across the country.

For their part, union leaders were attempting to regain favor among a growing layer of African American workers who were bitter about racism in the labor movement. Black workers often held the most physically difficult and worst paid jobs in union shops--and growing numbers of them were critical of union officials.

Nevertheless, the Unions to End Slums took off in Black communities across Chicago. From 1966 through 1969, tenant unions sprang up on both the West Side and South Side. They challenged high rents and miserable building conditions, and, most importantly, forced landlords and owners to sign collective bargaining agreements that linked payment of rent to apartment conditions.

IT MAY seem remarkable today, but tenant unions across Chicago in the late 1960s compelled landlords who owned thousands of apartments to sign agreements. Through a combination of picketing, sit-ins, rallies and rent strikes, the Chicago tenants movement publicized the slum conditions that were ubiquitous in poor Black neighborhoods across the city--and landlords frequently bowed to the pressure.

Tenant unions typically formed when activists surveyed residents in their buildings about which conditions bothered them most. These surveys became the basis of the bargaining agreements with landlords. Tenant activists also held hearings about building conditions and invited landlords to defend themselves against charges of being slumlords.

As early as 1966, the East Garfield Park Union to End Slums was successful in compelling West Side slumlords into signing a collective bargaining agreement that allowed 1,500 tenants to withhold rent and named the union as their sole bargaining agent. This one-year agreement was the first of its kind in Chicago.

In August 1967, when it was time to renew the agreement, the landlords decided to sell the building rather than sign a new contract with reduced rent. The new owners quickly signed the contract for fear of a rent strike. The landlords agreed that rent payments would be tied to conditions, and that tenants would have the right to withhold payment if the building went into disrepair.

There was another dramatic struggle over tenant rights in 1966 when the Tenants Action Council (TAC) formed to fight landlord conduct in a housing complex in the Chicago neighborhood of Old Town. Black and white tenant-members of TAC were determined to resist their landlord, who used the common tactic of allowing building conditions to deteriorate so that white tenants would leave and be replaced by Black tenants paying higher rents.

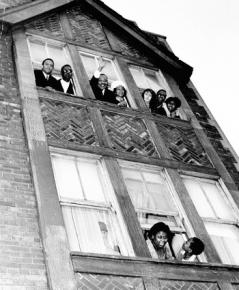

When the landlord attempted a mass eviction, TAC initiated a rent strike, leading to a highly publicized confrontation in September 1966. According to the Chicago Tribune, hundreds of protestors and tenants faced off against 80 police officers. While crowds jousted with the police outside of the building, TAC members inside chained themselves to radiators and refused to leave, often taking shifts with other tenant-members.

Wherever the Cook County Sherriff's deputies succeeded in removing the possessions of some tenants, TAC members and supporters gathered their belongings and returned them to the emptied apartment.

After about a week of these confrontations, building owners relented and agreed to sell the building to a buyer, who would sign TAC's collective bargaining agreement. The deal that ended the rent strike and protest included an agreement to stop all litigation against tenants who had participated in the strike.

THESE BATTLES represent just a fraction of the tenant union and rent strike activity of that era. From 1966 to 1969, the conservative Republican newspaper, the Chicago Tribune published more than 100 articles about tenant unions, rent strikes and the conditions that produced them.

In 1969, the Chicago Defender reported on a survey showing that in the first eight months of that year, tenant organizations "took action 67 times in 23 cities" against slum conditions and the absence of rights for tenants.

However, maintaining the tenant unions became increasingly difficult. Landlords brazenly used the lack of rights for tenants to simply evict renters who withheld rent. Moreover, because of slum conditions, there was high turnover in the housing as people moved out of their buildings as soon as they could. This inevitably created instability and turnover in the tenant unions.

As a result of this turnover, the SCLC focus on the Unions to End Slums quickly turned to "fair" and "open" housing as an alternative. While tenant unions focused on conditions in the inner cities and the buildings where Black people lived, the focus on fair and open housing looked to dismantle the barriers that kept African Americans out of white suburban areas and white neighborhoods in the cities.

To that end, the CFM organized marches into hostile white neighborhoods. While these actions received a lot of publicity from the media and political detractors, the marches were never very big--Black Chicagoans were not interested in living in neighborhoods where whites wanted to kill them. Moreover, the shift to focus on fair housing all but ignored the issue of combating the racist conditions of discrimination and exclusion in African American neighborhoods on the South and West Sides of Chicago.

In other words, activists asked why African Americans should have to move to white neighborhoods in order to get access to good housing, good jobs and good schools?

Clearly, Black people should be able to move wherever they would like. But the focus on fair housing failed to address the lack of resources in African American neighborhoods in the cities.

Those conditions, of course, persist some four decades later, and residential segregation remains pervasive. Now, as the foreclosure and economic crisis intensify these problems, it's time to renew the tradition of resistance represented by the Unions to End Slum and the formation of tenant unions across Black Chicago.

Their fight--the struggle to improve conditions in African American communities--is just as urgent today.