How the movement brought down a president

describes how the movement against the U.S. war on Vietnam gained strength, handing the empire its most bitter defeat.

THE OPENING weeks of Donald Trump's presidency have been a whirlwind of reactionary executive orders, revelations about contacts between Trump's campaign and Russian officials, open warfare between the White House and U.S. intelligence services, and Trump's furious attacks on the media for printing leaks from his administration.

And then there are the protests.

There was the Women's March on Washington, with sister demonstrations across the country and around the world. In the following days, there were spontaneous eruptions in opposition to Trump's bigoted executive orders targeting Muslims and the undocumented.

As Trump's approval ratings sink further, there's speculation that Trump could be impeached. It's still far-fetched--but not as far as it used to be, according to British bookies, who doubled the likelihood to nearly 50 percent that Trump would be out of office before his first term was up.

All this begs the question: What would it really take to bring down Donald Trump? To answer it, it's worth looking back four decades to the last--and only--time a president was forced to resign. What factors compelled Richard Nixon to leave office in disgrace in 1974?

THE IMMEDIATE crisis that triggered Nixon's eventual resignation was the attempt by the White House to cover up its role in the burglary of the Watergate office complex in Washington, D.C.,

Five men carrying bugging devices and a large wad of cash were caught in the middle of the night in the Democratic Party's national headquarters in the Watergate complex. Four of the men had ties to the CIA and had also taken part in the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in 1961.

When the ties between the burglars and Nixon's Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP) became public, the wheels were set in motion toward impeachment.

But the larger context of the Watergate scandal is essential to understanding Nixon's downfall.

In his book The War Within: America's Battle Over Vietnam, author Tom Wells cites the recollections of Roger Morris, a National Security Council staffer under Nixon. "Watergate--the whole generic beast--is a product of the administration's insecurity and paranoia fed by the war in Southeast Asia and by an inability to cope with that dissent, and [by] these perceptions of dissent widening around it in an almost conspiratorial way," said Morris.

In fact, the scandal was driven by "excessive concern over the political impact of demonstrators," a desperate bid to stem leaks from the White House (sound familiar?), and "an insatiable appetite for political intelligence," according to the testimony by John Dean, a Nixon operative, before the Senate committee that investigated Watergate.

The same men who broke into Watergate also broke into the home of Daniel Ellsberg, the Pentagon employee who leaked the Pentagon Papers exposing U.S. war strategy in Vietnam, in an unsuccessful bid to stop further leaks to the press from him.

Thus, a full recounting of Nixon's downfall must start with the story of how an antiwar movement that had begun as a tiny minority barely a decade earlier grew to involve practically every strata of American society.

THOUGH THE antiwar movement began in the mid-1960s with handfuls of activists debating what if anything could be done to protest the war, the Black freedom struggle of the previous decade served as a beacon of inspiration.

The civil rights movement had already shown that dedicated masses of people had the power to arouse public outrage and mobilize sufficient pressure to bring change, even in the face of government intransigence.

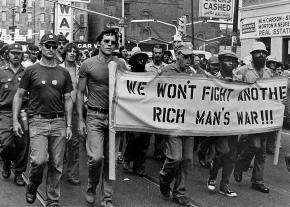

There were three main elements that ultimately led to the U.S. defeat in Vietnam and Nixon's unraveling: the Vietnamese resistance to the U.S. military machine, the revolt of U.S. soldiers and sailors within the military machine itself, and the popular mobilizations that spread from campuses into society at large.

In a 1965 speech, Malcolm X captured in his typically blunt style the bravery and resilience of the Vietnamese resistance to the American war drive. "Little rice farmers, peasants, with a rifle--up against all the highly mechanized weapons of warfare--jets, napalm, battleships, everything else, and they can't put those rice farmers back where they want them," he said. "Somebody's waking up."

As Joel Geier explained in a 2000 article "Vietnam: The Soldiers' Revolt" in the International Socialist Review, the U.S. military couldn't devise a strategy to defeat Vietnam's guerrilla fighters, who carried out hit-and-run on American targets by night and melted back into the countryside and their roles as peasant farmers during the day.

In this form of guerrilla war, there were no fixed targets, no set battlegrounds, and there was no territory to take. With that in mind, the Pentagon designed a counterinsurgency strategy called "search and destroy." Without fixed battlegrounds, combat success was judged by the number of NLF [National Liberation Front] troops killed--the body count...For each enemy killed, for every body counted, soldiers got three-day passes and officers received medals and promotions. This reduced the war from fighting for "the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese" to no larger purpose than killing.

In January 1968, the NLF and the North Vietnamese Army deployed a combined force of some 70,000 and fought to win the national capital of Saigon, along with the capital cities of 34 provinces. Relying on broad popular support to maintain the element of surprise, the Tet Offensive dealt a major political blow to the American war effort, even if it failed to achieve lasting military results.

The scale of the uprising against the U.S. military and the South Vietnamese government demonstrated before the eyes of the world that all the talk out about collapsing support for the NLF and a war effort on the verge of breakthrough success was simply lies.

Though the U.S. eventually rebuffed the offensive, the military relied on the utmost brutality to do so, using the same scorched-earth tactics in the cities that it had used to crush resistance in the countryside.

According to Nick Turse's Kill Anything That Moves, the U.S. counteroffensive left more than 125,000 homeless in Saigon and unleashed "an astonishing 600 tons of bombs, plus barrages from artillery and tank cannons" in the southern city Hue, destroying 80 percent of its built structures. More than 14,000 civilians were killed, mainly by U.S. fire, and some 627,000 became homeless.

Though it didn't become public until a year and a half later, the My Lai Massacre, in which a company of U.S. soldiers massacred hundreds of unarmed villagers, came to stand as the most shocking atrocity in a war full of shocking atrocities. It was carried out six weeks into the U.S. counteroffensive against Tet.

The counteroffensive also produced an especially harrowing turn of phrase that captured the essence of the U.S. war strategy. The commanding officer in charge of recapturing Ben Tre in Kien Hoa province explained the absolute devastation of the town to reporters by saying, "We had to destroy the town to save it."

U.S. SOLDIERS also absorbed the meaning of Tet, stepping up their own resistance to the U.S. war drive in response. After all, if the war wasn't winnable, why should any soldier risk his life to fight it?

If U.S. soldiers had, prior to Tet, turned their officers' commands to "search and destroy" into missions to "search and avoid," many turned to outright disobedience after the invasion.

By June 1971, the Armed Forces Journal reported that the ranks were in a state of open revolt:

Our army that now remains in Vietnam is in a state approaching collapse, with individual units avoiding or having refused combat, murdering their officers and noncommissioned officers, drug-ridden, and dispirited where not near-mutinous...[C]onditions [exist] among American forces in Vietnam that have only been exceeded in this century by...the collapse of the Tsarist armies in 1916 and 1917.

Whole units began discussing and debating the war among themselves, and some ended up deciding en masse to refuse to go on patrols. Black soldiers--emboldened by the civil rights movement, yet assigned to the most dangerous tasks by racist commanding officers--were particularly drawn to the growing revolt within the U.S. military.

As disaffection grew, some soldiers targeted gung-ho officers looking to enhance their opportunities by upping their number of kills with aggressive patrols rather than the Vietnamese resistance. By some estimates, 25 percent or more of the officers and noncommissioned officers killed in Vietnam lost their lives to "fragging"--which took its name from the fragmentation grenades rolled under a commanding officer's bunk.

THE REVOLT in the ranks of the U.S. military was decisive in U.S. military leaders reaching the conclusion that they couldn't continue to prosecute the war. But that revolt would have been unthinkable without the massive civilian antiwar movement, which helped to expose the doublespeak of the American government and military.

The movement also built GI coffeehouses and an entire counter-narrative to the lies regularly emanating from the Pentagon to show soldiers who refused to fight that they could find a whole community ready and willing to support them.

The first acts of the antiwar movement had been a series of teach-ins on college campuses in the spring of 1965 that drew thousands of students into discussions about the war just as Democratic President Lyndon Johnson ordered stepped-up bombing of North Vietnam and the first U.S. ground troops landed in South Vietnam.

At the teach-ins, which initially featured debates with Johnson administration officials until the officials stopped showing up because they failed to convince anyone, antiwar faculty and students engaged thousands of students.

The teach-ins focused attention on the many contradictions of the U.S. war effort--killing poor peasants in the name of peace, propping up despised dictators in the name of "spreading democracy," destroying villages in order to save them.

On October 15, 1969, some 2 million people participated in hundreds of local actions across the U.S. Many large cities had rallies of tens of thousands, while students wore armbands on campuses. A month later on November 15, the largest demonstration in U.S. history up to that point took place in Washington, D.C., drawing between 500,000 and 750,000 people.

The White House carefully managed media perceptions, asserting that Nixon paid no attention to the protests and had spent the afternoon watching college football. But as later investigations by journalists and historians revealed, Nixon was distraught over the size of the mobilizations.

"The demonstrators had been more successful than they realized, pushing Nixon and his National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger away from plans to greatly escalate the war, possibly even to the point of using nuclear weapons, and back toward their 'Vietnamization' strategy of propping up the Saigon regime," author Gerald Nicosia wrote in Home to War: A History of the Vietnam Veterans' Movement.

The protests grew even more intense in response to the U.S. invasion of Cambodia in early 1970, which sparked a student strike. The police and National Guard were called out to confront student protesters.

On May 4, the National Guard killed four and wounded nine students at Kent State University in Ohio. Ten days later, city and state police killed two students and wounded 12 at Jackson State, a historically Black college in Mississippi.

Rage at the killings of unarmed students further accelerated the outpouring of antiwar protests. All told, some 8 million students took part in strikes that affected 1,350 colleges in May alone. "Faculty and administrators joined students in active dissent, and 536 campuses were shut down completely, 51 for the rest of the academic year," wrote Wells in The War Within.

Two years later, Nixon would win reelection in the 1972 election, driving the antiwar movement and other activists into a state of near-total despair. Yet the internal strife and generalized sense of crisis surrounding the administration led a paranoid president to embrace a scorched-earth war strategy--in Vietnam, against the press and against his political rivals, both real and perceived.

Combined with the lack of any strategy to avoid military defeat, the U.S. war in Vietnam metastasized a Cold-War era confrontation with a marginal player into a military and political crisis that dealt a defeat to the world's main superpower--and ultimately brought down the world's most powerful head of state.