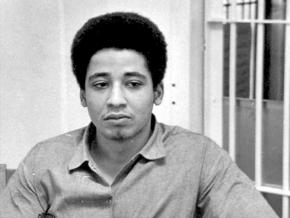

The murder of a Soledad Brother

looks at the legacy of Black Panther and revolutionary prisoner George Jackson on the anniversary of his murder in 1971.

GEORGE JACKSON was murdered by prison guards on August 21, 1971. Half a century later, his story deserves to be known by a new generation of activists.

Jackson was born on September 23, 1941, in Chicago. He was raised by a loving mother and father, and given particular attention by his grandfather, George “Papa” Davis. But at age 15, Jackson was imprisoned at a youth facility in California after several juvenile convictions.

“Capture, imprisonment, is the closest to being dead that one is likely to experience in this life,” Jackson later wrote in his book Soledad Brother. “When told to do something, I simply played the idiot and spent my time reading. The absentminded bookworm, I was in full revolt by the time seven months were up.”

At age 18, Jackson was convicted on dubious evidence of a gas station robbery of $70. “I was captured and brought to prison when I was 18 years old because I couldn’t adjust,” he would later write.

Based on prior arrests, Jackson was sentenced to between one year and life in prison and shipped off to California’s notorious San Quentin prison. The indeterminate sentence, declared the judge, would incentivize good behavior.

GEORGE JACKSON, however, was anything but “good” in prison in the view of prison officials.

He organized sit-ins against segregated cafeterias and taught martial arts to other inmates to fight back against the ever-present, abusive prison guards. Introduced to radical politics by fellow prisoner W.L. Nolen, Jackson was soon leading study groups on Marx and Mao, and became a revolutionary.

“I met Marx, Lenin, Trotsky, Engels, and Mao when I entered prison,” Jackson would later write to his supporters, “and they redeemed me.”

While in prison, Jackson was appointed “field marshal” by the Oakland chapter of the Black Panther Party, and was tasked with recruiting more prisoners.

Throughout the 1960s, Jackson wrote frequently from behind bars about the consciousness of prisoners. He wrote in 1969:

There are still some Blacks here who consider themselves criminals — but not many.

Believe me, my friend, with the time and incentive that these brothers have to read, study, and think, you will find no class or category more aware, more embittered, desperate or dedicated to the ultimate remedy — revolution. The most dedicated, the best of our kind — you’ll find them in the Folsoms, San Quentins and Soledads. They live like there was no tomorrow. And for most of them there isn’t.

In 1966, Jackson, Nolen and a prisoner named George “Big Jake” Lewis were alleged to have founded the “Black Guerilla Family” — a prison and street gang — from inside San Quentin.

This is contested history, however. For decades, attaching Jackson’s name to an active gang allowed the California Department of Corrections (CDC) to deem as contraband all material related to the Black revolutionary.

On January 13, 1970, Nolen and two other Black prisoners were killed by a corrections officer at Soledad prison. Three days after the killings were ruled justifiable homicide, a guard named John V. Mills was killed. Despite a lack of evidence, Jackson and two other prisoners — Fleeta Drumgo and John Wesley Clutchette — were charged.

Together, the three became known as the “Soledad Brothers.” A conviction spelled an execution in the gas chamber at San Quentin. The state of California was trying desperately to kill its incarcerated revolutionaries.

THINGS QUICKLY got worse.

On August 7, George’s brother, Jonathan, a 17-year-old high school student from Pasadena, took several hostages at the Marin County courthouse, including a judge, and demanded freedom for the three incarcerated men. Four people were killed in the ensuing shootout, including Jonathan and the judge.

Hundreds of miles away, Angela Davis — who had been recently fired from the University of California-Los Angeles for “inflammatory language” — was charged in relation to the shootout because the guns used by Jonathan were registered in her name.

Upon her capture, Richard Nixon congratulated the FBI for apprehending “the most dangerous terrorist” in the country. Davis would later be acquitted in a trial that would go down in the annals of the Black Power movement.

Jackson would dedicate his first book — the collection of writings and letters titled Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson — to Jonathan, Angela and his mother, Georgia Bea:

To the man-child, tall, evil, graceful, bright-eyed, Black man-child — Jonathan Peter Jackson — who died on August 7, 1970, courage in one hand, assault rifle in the other; my brother, comrade, friend — the true revolutionary, the Black communist guerrilla in the highest state of development, he died on the trigger, scourge of the unrighteous, soldier of the people; to this terrible man-child and his wonderful mother Georgie Bea, to Angela Y. Davis, my tender experience, I dedicate this collection of letters; to the destruction of their enemies I dedicate my life.

Soledad Brother sold over 400,000 copies and could be purchased at prison canteens across the country.

JUST OVER a year after Jonathan’s death, George followed his brother to the grave.

On August 21, 1971, Jackson was shot and killed by guards at San Quentin during what authorities alleged was an escape attempt. Somehow, they claimed, Jackson had smuggled a gun into the prison.

But the story kept changing — the police couldn’t get their story straight or explain how Jackson got the gun past the searches he was subjected to, or why he would try to escape moments after meeting with is lawyer.

At the time of his death, Jackson had spent 11 of his 29 years — and almost all of his time as an adult — behind bars.

“I must follow my mind, there is no turning back from awareness,” wrote Jackson. “If I were to alter my step now, I would always hate myself...I would die as most of us blacks have died over the last few centuries, without having lived.”

Jackson, like so many rebels before and after him, was murdered by the state. His death was condemned and mourned, and inspired a generation of activists.

“No Black person will ever believe that George Jackson died the way they tell us he did,” wrote author James Baldwin. Bob Dylan would eulogize Jackson in song, singing of his “tears in my bed” upon hearing the news.

While Jackson’s politics, like the Panthers’, were a mix of revolutionary and nationalist influences, as Guyanese historian and activist Walter Rodney wrote one year after his murder:

The greatness of George Jackson is that he served as a dynamic spokesperson for the most wretched among the oppressed, and he was in the vanguard of the most dangerous front of struggle...[He] knew well what it meant to seek for heightened socialist and humanist consciousness inside the belly of the white imperialist beast.

The great Trinidadian author and revolutionary C.L.R. James called Jackson’s writings in Soledad Brother “the most remarkable political documents that have appeared inside or outside the United State since the death of Lenin.”

In response to Jackson’s murder, thousands of miles away in upstate New York, prisoners at Attica staged a show of solidarity.

Journalist Heather Ann Thompson describes the morning after Jackson’s murder, when more than 800 prisoners gathered in the cafeteria and sat silently, not touching breakfast. Each one had a black shoelace tied around his bicep. One month later, Attica would soon erupt in one of the most inspiring prison rebellions in history.

WHEN A teenage George Jackson was sentenced in 1960, he became one of nearly 200,000 people incarcerated in the U.S. When he was murdered in 1971, there were an additional 100,000 men and women behind bars.

Fast forward, and the U.S. today holds some 2.2 million people behind bars, with an additional 5 million under the control of parole and probation. According to the recent film The Survivor’s Guide to Prison, one-third of all incarcerated females globally are in the United States, and 13 million Americans are arrested each year.

Today, the spirit of George Jackson haunts our incarceration nation. In many prisons, any object referencing George Jackson or the Soledad Brothers is considered contraband, so powerful and inspiring are his ideas.

In 2005, then-California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger invoked Jackson’s name as one of the reasons that prison activist and radical Stanley “Tookie” Williams should be executed.

In the words echoed by dissidents and revolutionaries across many times and many spaces, “you can jail a revolutionary, but you can’t jail a revolution.” The legacy of George Jackson is proof.