1968: The strike at San Francisco State

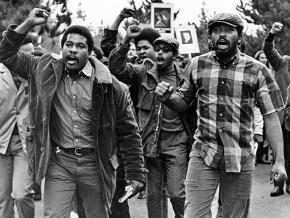

Fifty years ago, students at San Francisco State embarked on a campus strike that lasted five months — the longest student strike in U.S. history. Led by the Black Student Union and Third World Liberation Front, the strike was a high point of student struggle in the revolutionary year of 1968. It was met by ferocious repression, but the strikers persevered, and won the first College of Ethnic Studies in the U.S.

As part of Socialist Worker’s series on the history of 1968, current San Francisco State University Professor Jason Ferreira — the chair of the Race and Resistance Studies department in the College of Ethnic Studies and author of a forthcoming book on the student strike and the movements that produced it — talked to and about the story of the struggle and the importance of its legacy for today.

WHAT WAS unique about San Francisco State that made it an epicenter of struggle?

ONE OF the things that made San Francisco State unique as opposed to Berkeley or some other places is that it was a commuter school. The students were older, and it was a working-class school. Among the type of students who went to San Francisco State, not only did many have work experience, but they also had political experience that they brought with them to the campus.

The Black Panthers were a tremendous influence on what happened at San Francisco State, with many of the members of the Black Student Union (BSU) being early members of the party. So there’s an intimate relationship between the BSU and the Black Panther Party.

The SF State campus itself was a really exciting place. It was an epicenter for a lot of activism, a lot of organizing, a lot of culture, a lot of hippies, a lot of dope, a lot of poetry. It had everything, so it was a very exciting place to be.

WHAT STUDENT groups were active on campus?

THERE WERE four core groups of students. There was the BSU, the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF), Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Programs.

The TWLF was a coalition of student organizations of color. In many ways, it was formed by the BSU, but it also includea a Latin@ student organization (LASO), a Mexican American student organization (MASC), the Filipino organization called PACE and the Intercollegiate Chinese for Social Action (ICSA).

The TWLF was formed based on the political principle of Third World solidarity, which is animating Cuba, Algeria, Tanzania and Vietnam. So it’s no coincidence that they called themselves the TWLF — like the National Liberation Front in Vietnam. They were all internationalists — not necessarily Marxist, but internationalist.

The BSU created the TWLF partially out of principle and partially because they knew that in the struggle that was going to unfold, they would need alliances.

Socialist Worker contributors remember the great struggles of the revolutionary year of 1968 — and the lessons they hold for today.

1968: A Revolutionary Year

1968: The year that changed everything

1968: Tet and the watershed in Vietnam

1968: When King’s murder set off the uprisings

1968: Revolution reaches the heart of Europe

1968: A revolt blooms behind the “Iron Curtain”

1968: SDS and the revolt of the campuses

1968: The rise of the Red Power movement

1968: A war on dissent in the streets of Chicago

1968: Women’s liberation takes the stage

1968: The massacre in Tlatelolco

1968: The Nixon backlash and the “silent majority”

1968: The strike at San Francisco State

Plus, they could also see that the other students of color on campus weren’t as politically developed — that their consciousness had not come along as far as the Black Power movement had. Other groups of color were just forming the Asian-American or Latino movements in the late 1960s, whereas the Black community had gone through this a few years before, due to Malcolm X and the Black Consciousness movement.

So the BSU created the TWLF as a way to support that political development.

There were also the white student groups: SDS and the Programs. There was a lot of tension between these two groups.

The Programs were trying to build student power and community involvement programs, where they were connecting student-organizing efforts like a Tenants Union in public housing in San Francisco, while trying to give students credit to be organizing.

Then there was SDS, which was more confrontational — like “F*** the pigs, kick ROTC off campus, kick the Dow Chemical recruiter off campus.” SDS at SF State had principally been taken over by Progressive Labor. So SDS viewed students in the Programs as reformist, and those in the Programs looked at SDS as ultra-left and sectarian.

WHAT WAS the source of discontent on campus and the conditions that led to the strike?

THERE’S SO much focus on the strike itself because it’s so spectacular. The institution was shut down for four-and-a-half months, the Tactical Squad was out there every day cracking skulls.

But it’s important to understand that the strike was just a culminating moment, when the crisis came to a head. There were many contributing factors.

The BSU students had been organizing for years, developing alternative educational experiences, within the Experimental College at first, and later the tutorial programs that connected them to the community. The BSU students ran this program and were tutoring hundreds of kids in the Mission and Fillmore, teaching them the basics, but also teaching them Black Power.

Out of these diverse experiences, a unique and revolutionary Black Studies curriculum began to cohere. However, the administration was threatening to pull funding for these working programs.

There was also an English instructor, George Murray, one of the Central Committee members of the Black Student Union, who was a longtime student at State and a graduate student by the late 1960s, but he was also Minister of Education for the Black Panther Party.

In the summer of ’68, George traveled to Cuba and gave a speech there where he basically said — I’m paraphrasing here — that every U.S. soldier that dies in Vietnam is one less soldier we have to deal with in the streets of Detroit.” He was linking the Black liberation struggle with the struggle of the Vietnamese people.

Needless to say, when the Board of Trustees and then-California Gov. Ronald Reagan found this out, they were irate and tried to fire Murray. That was one catalyst for the strike.

In the spring of ’68, there was also a sit-in organized by SDS and TWLF where the goals were twofold: kicking the ROTC off campus was the big SDS demand, and the TWLF had a set of demands around recruitment and retention of Third World students — not only Black students but also students from the Mission and from Chinatown. That sit-in didn’t get the ROTC off campus, but it did get special admissions for students of color.

The SFSU campus president, liberal John Summerskill, made the promise, but as soon as he made it, he resigned. As a result, over the course of the summer and into the fall, those special admits never materialized. This also added to the rising level of frustration.

So the BSU wasn’t getting their Black Studies program as promised, and funding for the programs they were involved in with the community was being threatened by Sacramento and by the Board of Trustees. One of their prominent members, George Murray, was threatened with being fired.

Plus, members of the Third World Liberation Front weren’t getting the special admits they had been promised, and on top of that, they were beginning to make a demand for Third World studies, La Raza studies and Asian American Studies.

So when the catalyst happened — with George Murray being fired from teaching — the BSU went out on strike. The BSU issued 10 demands, and the TWLF added five demands, going out on strike along with the BSU.

I think what made the strike so unique is the way that white students on this campus followed the leadership of Third World students. On other campuses, it wasn’t that way — white students were in the leadership, and Third World students were maybe involved.

But this was a case where leadership and the demands were squarely in the hands of Third World folks. And white students supported and didn’t challenge that leadership. They didn’t say try to make this about student power or the war — they stayed focus on the BSU and TWLF demands’ — because, I think, those demands ultimately opened out to these broader issues of imperialism and the war.

WHAT WERE the demands of the strike?

REHIRING GEORGE Murray was one of the original demands of both the BSU and the TWLF. One of their five demands was to rehire George Murray, too.

If you look at the demands, they’re very specific: We want this woman fired, we want Nathan Hare given a permanent position, we want this number of faculty positions. It wasn’t “we want global revolution” or anything like that. This was intentional because the students wanted to be able to struggle over something concrete and be able to win a base for later.

During the course of the strike, they continually restated the demands and said they were nonnegotiable because this is what the community needs. They argued that the demands reflected the fight against racism: It’s about self-determination and power. They weren’t looking for crumbs — they wanted the power to determine who the faculty was and the type of curriculum being taught.

HOW DID the strike unfold? Can you talk about the strikers’ tactics?

UP UNTIL the fall of ’68, some of the dominant tactics of the student movement were occupations and sit-ins. The BSU said we’re not going to do that — we’re going to embrace the tactics of guerrilla warfare, like Che and the Vietnamese.

What did they mean by that? They didn’t mean being armed per se, but they pointed out that sit-ins were largely symbolic. At most, you hold a space for a day or two days or three days. At a certain point, the institution wears you down. Maybe you get immediate attention when they arrest you, but in the end, you display your powerlessness.

The BSU was looking at what happened at Columbia University in New York City in the spring of ’68. Stokely Carmichael had come out and given a talk at State, where he said that the Columbia students made a dent, but they didn’t change the power relations on campus.

The BSU decided that they were going to shut down the university down. They weren’t just going to occupy space. But they didn’t just go out on strike by picketing the campus. Instead, they decided to use guerrilla warfare tactics — we advance when the enemy retreats, and when the enemy advances, we retreat.

This meant having mobile forces. One of the first things they did in the first week was create disruptions all over campus: stink bombs clogging up toilets, going to classes and saying, “Don’t you know we’re on strike?” and doing some political education.

The logic was: If we can’t have the education we want, you’re not going to get the education that you’ve been getting. We’re going to disrupt this classroom, but when the police come — boom, we’re gone.

Those were the initial tactics during the first week. SDS and the movement people supported the strike. But it took about a week before things developed.

HOW DID the strike build support at this point, and what role did police repression play?

THE BSU had a press conference about one week into the strike, and the cops came onto campus and just started beating people — members of BSU in particular. BSU leader Nesbit Crutchfield got hit over the head for everyone to see.

Pandemonium ensued on campus. Some faculty supported the students, even if they didn’t necessarily agree with the tactics — they supported the ideas behind the strike. So the faculty got in between the police and the students on that chaotic day.

From that point on, the biggest recruitment factor for the strike was probably the police because they overreacted. They decided that they were going to shut the militants down, and it got to the point that the Tactical Squad was pulling police not just from San Francisco, but Santa Cruz, Vallejo and all over the region.

And of course, the cops relished the opportunity to rough up Black folk, hippies, people who were challenging gender conventions with long hair, people who were peace activists. They saw San Francisco State as a place to vent their racist vitriol. You could feel it, like the heat of their hatred radiated off of them.

This began to politicize more and more students, who saw that law and order wasn’t a good response to legitimate demands.

The BSU and the TWLF started doing more education, with a convocation to explain their demands. And they started bringing the community in, from the Mission and the Fillmore and Chinatown.

There was a tremendous transformation. These apolitical students — everyday people who you would have seen on campus — were saying “F*** the pigs” and throwing rocks at the cops.

Part of this had to do with the broader environment, including the war in Vietnam. Ronald Reagan famously said in a press conference that San Francisco State was a domestic Vietnam. There’s certainly an exaggeration in that — obviously the things happening in Vietnam, like napalm and the massacre at My Lai, weren’t happening at San Francisco State.

But Vietnam was undeniably a subtext for what was happening at State, both in terms of the fact that a group called the Third World Liberation Front was fighting for educational self-determination and the empowerment of oppressed people — and also with the state’s response that we need to crush these militants and dissidents because they represent anarchy,” just as they were doing with the Panthers.

So Vietnam was the subtext. For those everyday students who weren’t militants or radicals themselves, it was difficult to remain neutral when your campus is being occupied militarily every single day. The Tac Squad was out there with huge batons and riot shields and helmets, and they’re looking to pick off members of the BSU or TWLF, or crack the skull of some protesting student.

WHAT WAS the response of the administration to the student strike?

In the spring of ’68, as I mentioned, the president of SF State, John Summerskill, resigned after that TWLF/SDS sit-in. John Summerskill was a liberal; he was a Kennedy boy. But liberalism was under attack by this point in the movement.

These days, we tend to think about those liberal politics of the 1960s, but the movements by this point had realized that liberals were part of the problem. Liberals just want stability, they don’t want to change the power dynamics.

So the liberals were caught in the middle. You had, on the one hand, the right wing, with Reagan and the law-and-order people, and on the other hand, there was the left, with powerful movements pushing for radical demands. They didn’t just want reforms. They wanted power — real, meaningful and deep democracy.

The liberals were caught in the middle, pushed and pulled both ways. They might want to help Black people, but they also had a responsibility to and a relationship with the forces on the right that didn’t allow them to do that.

So when John Summerskill resigned in the spring of ’68, and they brought in another liberal: Education professor Robert Smith. Through the summer and into the fall, he was the president.

But as the strike unfolds, he had the right wing telling him to not close the campus — to bring in the police to maintain order for the “good students” who want to study and kick out the dissident students. Meanwhile, the students are telling him to shut the campus down until we resolve these issues.

Smith tried to occupy a middle ground, with school still in session, but creating spaces where everyone could come and talk about the issues. He proposed a convocation where anybody who was interested could come and learn about the issues of the strike. That didn’t satisfy the right, of course, and it didn’t satisfy the striking students.

The BSU and TWLF took advantage of the crisis and used the convocation as a platform to educate the nonpolitical students about the origins of the strike. They ultimately walked out, and Robert Smith resigned.

Reagan brought in a new president — another San Francisco State faculty member named S.I Hayakawa. What a character this guy was! He was a megalomaniac who decided that he was going to be the man to shut this down and instill law and order. He was also, as a Japanese-American, a person of color, so the right absolutely loved him because he created all these new dynamics.

So now you have a man of color in the big seat, talking about who the responsible students were, and who the irresponsible students were. But you also have Asian-American students, Black students, Native students and Latino students continuing to push him — they weren’t falling for a symbolic “nonwhite face in a high place.”

From the point Hayakawa was hired to the end of the strike, the administration was all about “law and order”: Use the police to shut down and crush the campus movement.

Importantly, the strength of a lot of the student organizations was in their community programs: the tutorial and community involvement programs. Hayakawa started shutting down their sources of funds, so that dried up.

This is a classic counterinsurgency tactic — kind of like what the right did in the late 1970s and 1980s when it started unraveling social programs.

The New Deal and Great Society programs had all brought in students who had previously been excluded from campus. When that happened, they got politicized. As liberal and reformist as they might have been, these programs politicized people, got them involved in the community and kind of subsidized activism.

So the right wing decided that they were going to cut the programs off at their base, which was their connections to the community.

In the end, Hayakawa became the darling of the right. He eventually became a U.S. senator for California, and of course, his big claim to fame when he was a senator was pushing for English-only in California.

He had a Tam o’ Shanter hat, and that Tam o’ Shanter hat became a symbol for law and order. He became a celebrity of the right. He was flown out to meet with Richard Nixon because he was seen as the guy who wasn’t going to take shit from these militants — and he was a person of color.

HOW DID the students maintain momentum for the strike with so much repression?

THERE WERE days that it was very scary for people, and the big fear was that somebody was going to get killed. It was well-known that the police looked forward to taking out some of the strike leadership of the strike.

And this can’t be separated from the police’s simultaneous desire to neutralize the Panthers. There were raids on the Panthers office in the Fillmore happening during the Strike.

So it was very, very difficult. But when you’ve got 3,000 students, and sometimes up to 5,000, out there, that’s an inspiring way of boosting spirits.

Then there are dark days like January 23, 1969, when there was a huge bust and well over 400 people were arrested.

The leadership had to be very selective about what days they were going to go on campus, because they knew there were warrants out for Roger Alvarado, the TWLF spokesman, and Benny Stewart, the BSU chairman, and many others.

But it should be said that by this point in the struggle in the spring of 1969, the leadership of the BSU and TWLF were deeply engaged in the community. They had offices in the Fillmore and in the Mission, and they were engaging in many meetings with community leaders to intervene on behalf of the students. They were also organizing on a statewide level with Third World students on other campuses.

HOW SUCCESSFUL was the strike in shutting down the campus?

IT WAS never a hundred percent. But think about it: Even if students and faculty were still holding classes, imagine trying to go to your class, and you have to march through the Tac Squad and through 2,000 students out on the central square just to get there. It would be a little nerve-wracking.

LATER ON in the strike, the faculty walked out, too. Can you talk about how that developed and what effect it had on getting the administration to settle?

THE FACULTY had a long set of issues going back many years, which were connected to efforts to organize a union for faculty. The organization that was representing faculty at the time was a professional association — it wasn’t a real union.

There was a group of radical faculty at SF State that wanted a real union. Some had ties to the labor movement themselves. Some — many of them on the younger side — had ties to the wider movement.

That’s another thing to recognize about San Francisco State: Some of the faculty wanted to be there because they were young and hip and cool. They smoked weed and went to the jazz clubs. It wasn’t like Berkeley or Stanford or other places, where the faculty was stodgy and separate from the life of the community.

These people were young, some of them in the 20s, and they were politically involved. San Francisco State was a specific destination for them. This was another way in which the political and cultural life of the campus was interwoven with the political and cultural life of the city.

So the question of power was part of all of this. On the one hand, students at SF State were making specific demands challenging the power of the Board of Trustees and, quite frankly, the larger political economy of higher education in California. They were challenging the so-called Master Plan for Higher Education, in which students were tracked. Some students, mainly white and middle class ones, were tracked for the UCs, some people tracked to the CSUs, and then some people, mostly working people and people of color, tracked directly to the community colleges.

The demands of the TWLF and the BSU were challenging that system, and saying: “We want power; we want autonomy.” And the faculty wanted that power, too.

For years, the Board of Trustees had tried to control and centralize the educational process — to seize power away from individual campuses and away from faculty and students.

The faculty was fighting for the bread-and-butter issues of a trade union, too. They wanted better salaries, better working conditions, a grievance procedure — classic union stuff.

When the students went out on strike, there were already some faculty who had issues with the Trustees, and they supported the students. There was faculty, for instance, who tried to get between the police and the students at various times.

By December, they were telling the administration that they better deal with the students, or we’re going to go out on strike, too. But by that point, they didn’t want to deal with the students. Hayakawa was looking to crush the strike, not settle it.

So the faculty walked out in January. The San Francisco Labor Council sanctioned the strike, which meant that deliveries weren’t coming through and garbage was piling up across campus. Nobody was going to cross the picket line.

The authorities were becoming quite concerned that this could turn into some type of regional insurrection if the strike were to spread to the Fillmore, the Western Addition, the Mission, Bayview-Hunters Point. They feared that if the struggle deepened, they weren’t going to be able to keep it confined it to just the campus anymore.

So the community was involved, labor was involved, and other campuses were threatening strikes. One could argue that this is why we got a College of Ethnic Studies. The power in the street was just too strong.

WHAT WAS the outcome of the strike? What did the strikers win, and what did they lose?

THE STUDENTS got their demands for the most part — except that George Murray never came back to SF State.

In the middle of the strike, he was arrested. He was under constant surveillance, and he got pulled over driving in the South Bay. He had a gun in his car, which wasn’t surprising: he was the Minister of Education of the Black Panther Party, an organization undergoing intense political repression.

They used that as a pretext to throw him into jail. From jail, Murray became part of the negotiations to end the strike. But by that point, he left the party and became a minister.

The BSU and TWLF settled the strike, and they ultimately established the College of Ethnic Studies during the fall 1969 semester — which was composed of a Black Studies Department, La Raza Studies Department, Asian American Studies Department and, eventually, an American Indian Studies Department.

Then came the business of offering classes and hiring people. It was different at that time, because there really weren’t a whole lot of people with PhDs in La Raza Studies. So they often ended up hiring folks from the community to teach — or members of the Black Student Union who were graduate students.

But this campus/community relationship was actually fundamental to the mission of these early departments.

IN THE first year of Ethnic Studies, many of the original faculty were pushed out. Can you talk about how the administration was able to do that?

A LOT of the original faculty in Ethnic Studies either got fired, didn’t get rehired or got pushed out.

But have some perspective: This was after five months of that type of grueling strike, where there was so much sacrifice, where people’s personal relationships were damaged, where there was a level of paranoia and police infiltration. There was a real fatigue factor — people asked if they wanted to jump right back into that in the fall of 1969.

At the same time, some of the members of BSU, like Nesbit Crutchfield, were sent to prison on trumped-up charges. By the spring of 1969, 400-plus people had been arrested. That took the wind out of the sails of the movement. All of a sudden, you had to figure out how to represent 400 people in the courts, facing felony charges.

Some people, like members of PL, said that it was important to organize against the courts and represent themselves, to show how the courts are part of a class system. But there are a lot of other people who were arrested who just weren’t political in that way. They had been rounded up and thrown into jail, and the leadership of the BSU and TWLF felt a responsibility to defend these people.

There was a legal defense campaign that lasted a full year, which was draining, just representing these people, getting the evidence and lawyers together, trying to get the charges dropped. So in the fall of ’69 and into the spring of ’70, people were stretched thin.

And on top of that, some people started to look away from organizing on campus. They participated in all these struggles, like against the police in the Mission or defending the elderly at the I Hotel. So some people in the movement invested their energies into other spheres of struggle.

As a result, there wasn’t a strong defense of the people who were trying to build Ethnic Studies. In some ways, that created a vacuum, and the people who filled that vacuum — in my view and the view of many of the original strikers — were a combination of traditional bourgeois academics or cultural nationalists.

So people sort of burrowed down into their spaces and did their academic work, but it wasn’t connected to working-class struggles anymore in an organic way. Plus, the cultural nationalists were always critical of the Panthers — and, by extension, the BSU — anyway, because the Panthers worked with white folks or were Marxists or identified as Third World revolutionaries.

CAN YOU talk about the legacy of the strike 50 years later — both for our radical history and for how it shaped San Francisco’s struggles and grassroots institutions?

I TEND to talk about San Francisco as one of the global epicenters of an international revolutionary movement. Havana, Algiers, Dar es Salaam: those would be other ones. San Francisco is one of those places where the local and the international converge.

What happened at San Francisco State remade the city. I think of it as similar to the famous 1934 strike of longshore workers, and the impact that had on the political terrain of San Francisco.

What happened at San Francisco State in 1968 reverberated throughout the city. Many of the institutions bettering the city right now have connections to the strike — if not directly, then indirectly. People went from their experience at State and got involved in the community.

There were community health clinics started out of the strike, as well as KPOO, a people’s radio station. People from the Black Student Union were centrally involved in the politics of the Western Addition, and some of them joined together to start this radio station. It’s still standing today — still community-based radio.

Then, of course, there’s Los Siete de la Raza — many of the people who were involved in Los Siete de La Raza were connected to the student strike at SF State and the College of San Mateo.

Los Siete developed free breakfast for children and community health centers. They developed legal aid centers and put out a community newspaper called Basta Ya that ran for a couple years. After that, the organization dedicated more time to organizing workers at the point of production.

All of these things gave birth to and catalyzed community-oriented institutions. El Tecolote, a free bilingual newspaper, while not a Los Siete creation itself, represents the next iteration after Basta Ya. It was started by students at San Francisco State in the La Raza journalism class.

It served a need because Latinos continued to suffer from horribly racist coverage in the San Francisco Chronicle, which referred to Raza youth as dirty, Latin, hippy gangsters and so forth. So folks decided to create their own newspaper and report on their own community. El Tecolote still publishes out of the Mission District.

After the strike, some people got burnt out and decided that this academic thing wasn’t worth it. They got more involved in the community — in the struggle at the I Hotel, for example. Plus, in the fall of 1969, Native students were part of the occupation of Alcatraz Island.

So the strike produced a wave of energy that permeated the city: The I Hotel, Alcatraz, Los Siete, the Panthers — they were all connected to what happened at SF State and propelled forward by the strike, even if the struggles had national and international reverberations.

The other legacy that I would mention is the participation of Chinese students in the strike.

The experience of the strike led to dramatic changes within the community as folks began challenging the established leadership in Chinatown of the Chinese Six Companies. This leadership was very conservative, connected to the politics of Taiwan and the political right. Then suddenly, you had young Chinese students asking about who this guy Mao is, and working with youth in the community.

The politicization at State led to their deeper involvement in Chinatown politics, developing the voice of Chinatown youth and connecting with those people in the community who had been silenced — like the Communists who had a history going back to the 1930s in Chinatown, but who had been silenced and purged because of McCarthyism and the right-wing leadership.

So a new generation came to be the foot soldiers in a challenge to the traditional leadership in the community. This also happened in the Mission.

So when I say there’s a rich history and legacy of the SF State strike, it’s not confined to a syllabus or even to the campus itself. It’s in the neighborhoods of San Francisco, and it’s tied to both a national and international struggle.